Antonio Harris talked about the attack at the Northwest DC school publicly for the first time as he thanked workers at GW Hospital who saved his life.

WASHINGTON — The first thing security guard Antonio Harris heard when a sniper attacked the Edmund Burke School in Northwest D.C. in April was the windows shattering.

He raced to order the kids back inside – and then felt a searing pain in his right side.

On Thursday, six months after four people, including Harris, were shot at the school on Connecticut Avenue, the retired MPD officer returned to thank the doctors and nurses at George Washington University Hospital who saved his life.

It’s been our first chance to hear from him.

“I got hit right here,” Harris said, rubbing an area just below his rib cage.

Looking at him now, you might never guess Harris was the most gravely injured patient his trauma surgeon said he’s ever treated.

“I thought I got hit three to four times. But I only got hit once, and the round was just rattling around in my body,” he told reporters.

The sniper perched in an apartment above the school with four rifles and 400 rounds of ammunition. He rained 239 bullets down on children about to leave for the day – and the parents waiting to pick them up.

Harris fell to the ground and was swept up within minutes by officers from an emergency response team. He remembers passing out in the medic unit. He didn’t wake up from a coma for five days and spent three-and-a-half weeks in the hospital.

“Just give me a minute. I can do this,” wiping away tears as he spoke to surgeons, paramedics and hospital workers at GW’s 11th Annual Trauma Survivors Day. “I truly did not get to this day by myself,” he told them, pausing for long moments while his tears dropped to the podium.

To applause from about 100 people gathered to celebrate him and him and three other survivors, he said, “You save lives every day, every day!”

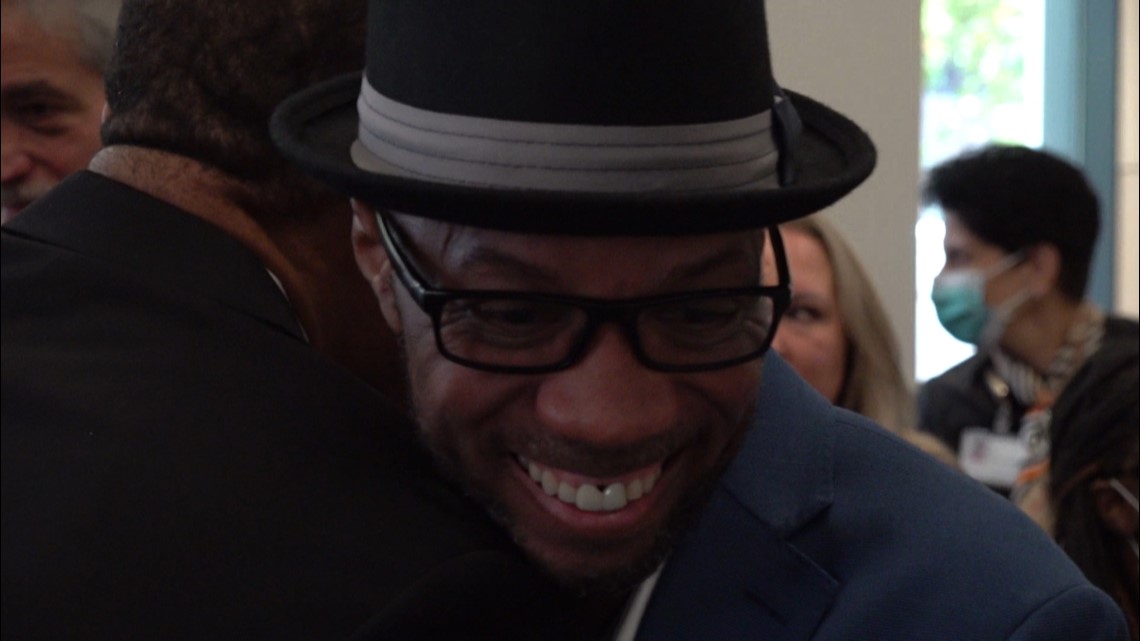

“I’m Haley. You probably don’t remember me; I was the trauma nurse that treated you,” a nurse told him. He didn’t remember, but he gave her a hug and a huge smile anyway.

How close was he to dying? “Oh, minutes,” said Babak Sarani, MD, GW’s director of trauma and acute care surgery, who treated him.

A single high-velocity round pierced Harris’s liver, kidney, and intestines. The trauma team pumped 85 units of blood into him. But he just kept bleeding. Until doctors inserted a balloon into his aorta to slow the flow.

“The catheter we put in him and kept in him for 20 hours is unheard of,” Sarani said. It made medical history. The REBOA catheter they used had never been left in a patient for more than about 3 hours. But as soon as the trauma team deflated it, “His blood pressure would tank in front of us,” Sarani said. He would have quickly gone into cardiac arrest.

After nearly a day, intensive care nurses were finally able to wean him off it.

Despite the ordeal, Harris has no second thoughts about rushing to save the children. “I was trying to tell them to go back inside, and I was trying to take cover. Then I got hit,” he said.

In 26 years as a police officer, he figured he repeatedly risked death or grave injury. But as a school security guard, he thought those days were behind him.

Still, he’s already been talking to schools about coming back to work. “I expect to be back in April. One year from the day I got shot,” he said, his face lighting up at the thought.

WATCH NEXT: Chief Contee says video of ‘sniper-style’ shooting shows gunman’s scope was tracking Edmund Burke students

“I don’t think we can say that it was not a school shooting,” Contee says when asked to classify a quadruple shooting in Van Ness on April 22.