Although the sinking of the Titanic in 1912 was a global tragedy, it wasn’t until 2012 — 100 years later — that there was a Mexican “vision” of the most famous shipwreck of the 20th century.

The new awareness that the ill-fated vessel had carried a Mexican politician, who was said to have saved a woman’s life, suddenly made this a Mexican story. And Mexicans love tall tales and legends.

But is this story a tall tale?

What has been verified without doubt is that Manuel Uruchurtu Ramírez did indeed die on the Titanic. However, whether or not the heroic story of him saving a woman’s life was true quickly became the focus of controversy after his story was revealed in a book published in 2012.

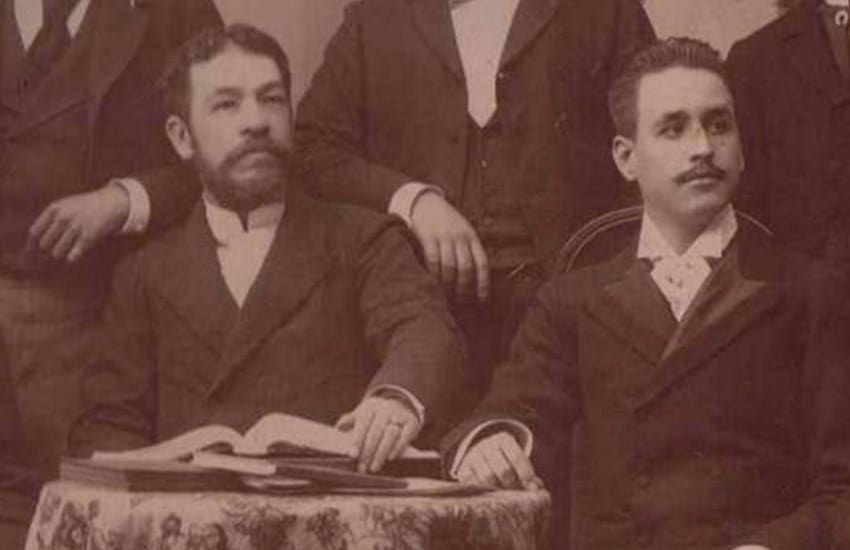

Uruchurtu was born in June 1872 in Hermosillo, Sonora, to a well-to-do family. As a young man, he traveled to Mexico City to study law at what is now the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM).

He married fellow student Gertrudis Caraza y Landero, a young Mexican woman of high social standing, and settled in Mexico City, where he started a law practice and he and his wife had seven children.

By the time of the Porfiriato — the dictatorship of President Porfirio Díaz (1876–80; 1884–1911) — Uruchurtu was well-established in national, cultural and political circles in Mexico. He was elected to the Mexican federal congress four times and was especially close to Díaz’s vice president, Ramón Corral, whom Uruchurtu considered his best friend and political godfather.

At the time of the 1910 Revolution, Uruchurtu’s financial and political status labeled him as one of the “catrines” — wealthy individuals who had well-defined ties to Díaz. In 1911, following Díaz’s overthrow, Díaz and his inner circle were exiled to France.

In February of 1912, Uruchurtu decided to travel to France aboard the Lusitania to visit with Ramón Corral and Díaz. Afterward, Uruchurtu next planned to go to Spain to learn more about the Spanish court system, which would help him with his international law practice.

But as Uruchurtu was in the Grand Hotel in Paris, packing for his side trip to Spain before returning to Mexico, Corral’s son-in-law, Guillermo Obregón — who was returning to Mexico himself — paid him a visit.

Uruchurtu had purchased a ticket on the SS France, but Obregón persuaded him to exchange tickets — saying he really shouldn’t miss out on an opportunity to be on the maiden voyage of the luxury ocean liner Titanic — which would leave a few days earlier.

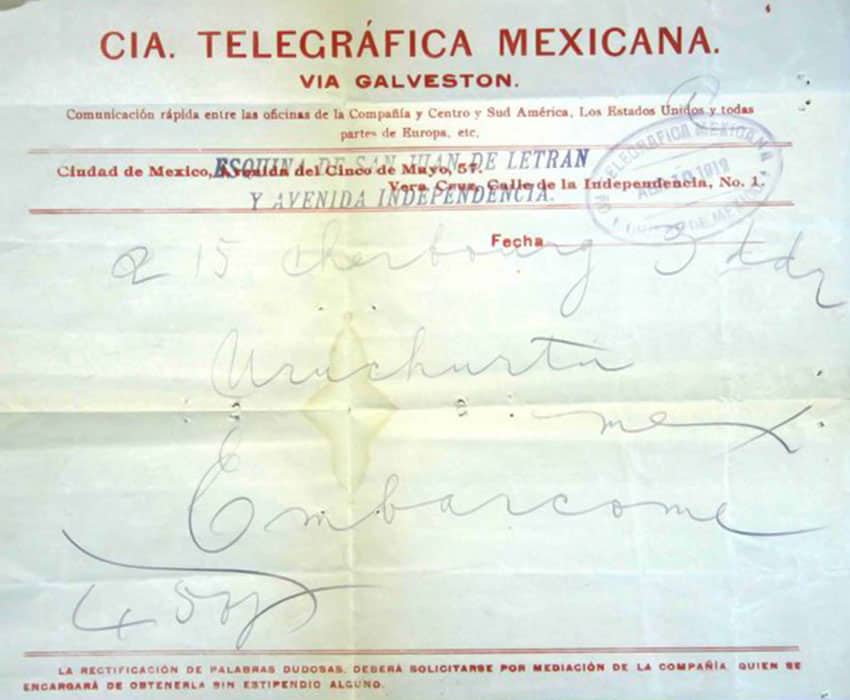

His final correspondence with his family consisted of a letter written to his wife from Paris, telling her that he was eager to return to Mexico but had to go to Spain first. He also sent his mother a picture postcard of the Titanic, telling her he would be sailing on that ship. And he sent a telegram to his brother right before he left with one word: Embarcome (I’m boarding).

Uruchurtu’s family never heard from him again.

At 2:20 a.m. on April 15, the “unsinkable” RMS Titanic — the largest and most luxurious ocean liner at that time — hit an iceberg 400 miles southeast of Newfoundland, Canada, and sank. The ship’s orchestra is said to have been playing the waltz from the operetta “The Merry Widow” as the Titanic took more than 1,500 passengers to a cold, watery grave.

Only around 700 survived.

Two weeks later, Uruchurtu’s wife Gertrudis received a telegram from the Mexican Telegraphic Company that her husband’s body had not been recovered.

For more than 30 years, Uruchurtu’s great-grandnephew Antonio Uruchurtu told the story of El Héroe Mexicano del Titanic (The Mexican Hero of the Titanic) — his ancestor, Manuel Uruchurtu — who sealed his fate with a noble act of chivalry. But what was Manuel’s supposed act of chivalry?

According to the story, Uruchurtu was offered a seat with the women and children on Lifeboat #11 due to his position as a member of the Mexican Congress and his role as a diplomat. Second-class passenger Elizabeth Nye, on her way to New York City, did not get a seat.

As the story goes, Nye pleaded with Uruchurtu to give her his spot on the lifeboat because her husband and child were waiting for her in New York. He complied, asking only that she tell his family how he died.

Antonio says Nye survived and came to Hermosillo in 1924 and told them the story of their ancestor’s chivalry, a story the family told around the kitchen table for years.

Based on this story, the City of Hermosillo issued an “Official Declaration of Manuel R. Uruchurtu as a Hero of Chivalry” in 2010, a decree that was ratified by the Sonora state congress. In 2011, Uruchurtu was also honored as a “Hero of Chivalry” by the Sonora Historical Society.

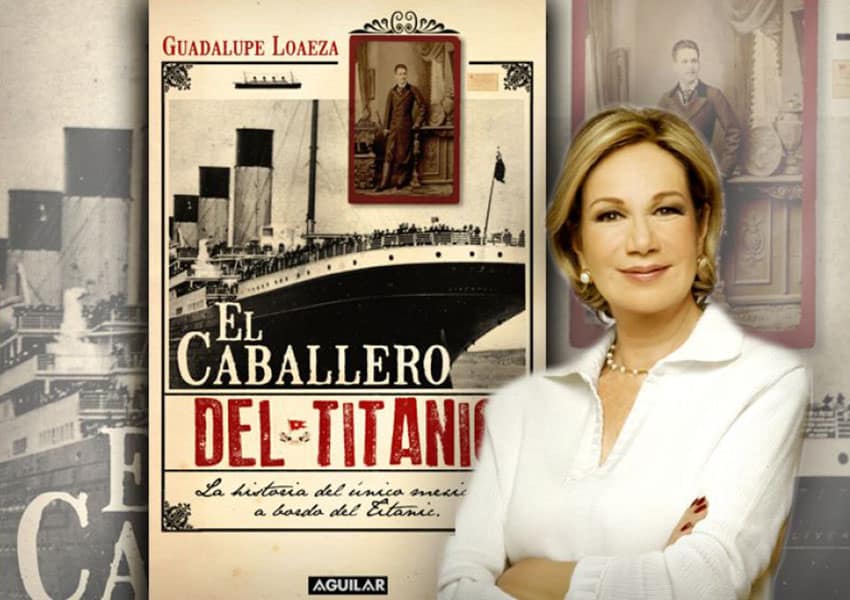

Alejandro Gárate Uruchurtu — another grandnephew — had also convinced author Guadalupe Loazea to write a book on Manuel Uruchurtu, for which Alejandro would receive a portion of the royalties. In 2012, “El Caballero del Titanic” was published sparking a firestorm of controversy.

Author Dave Bryceson, who wrote the biography “Elizabeth Nye: Titanic Survivor” said the story could not be true, citing 20 years of research he said proved that Nye’s husband and child had died before she ever boarded the Titanic and that she had never visited Mexico.

Furthermore, Uruchurtu’s granddaughter denied that the incident ever happened. The Titanic Historical Society — established in the U.S. in 1963 — said that they could find no evidence of this act of heroism — only that Uruchurtu was a passenger.

Mexican newspapers denounced the book, which they called fiction. Loazea herself finally said that considering the emerging revelations, she would not reprint the book — that it was based almost entirely on Gárate’s story without a single document to verify it as true.

Mexico’s history is full of legends and myths. Much of what we know about the last hours of the Titanic is also fiction. The famous James Cameron film “Titanic” — which was filmed in Baja California — centers on a fictionalized love story between the two main characters — Rose and Jack.

The sinking of the Titanic is a very human story filled with tales of love and loss, bravery and pettiness — of passengers who acted with chivalry and those who did not. That does not detract from our fascination with this 20th-century tragedy or from the credibility of the stories.

I prefer to believe the legend of Uruchurtu’s heroic act is true because it is the embodiment of the values of Mexicans — honor and chivalry — noble values that are highly respected in Mexico.

It also makes the sinking of the Titanic a very Mexican story.

Sheryl Losser is a former public relations executive and professional researcher. She spent 45 years in national politics in the United States. She moved to Mazatlán in 2021 and works part-time doing freelance research and writing.