In rural towns and counties across Northern California this past year, many fire departments were forced to stand by and watch as wildfires burned more than a million acres of land in neighboring communities. With no firefighters to spare, fire chiefs were forced to turn down urgent requests for help.

Waves of COVID-19 infections, growing numbers of early retirements and departures, a shrinking pool of applicants and a diminishing number of inmate crews led more than 100 chiefs of smaller rural and suburban departments to decline mutual aid requests for the Caldor Fire, the blaze that pushed through the El Dorado National Forest toward Lake Tahoe for nearly two months this fall.

Now, while the 2021 fire season that claimed over 3,000 structures and three lives appears to be over, those chiefs are raising concerns about potentially worse problems next year.

“We as chiefs talk about … how we are going to manage if this is the new norm,” said James Moore, whose staff at the Susanville Fire Department in Lassen County has dropped by a third in recent years and is at risk of new cuts next season. “My answer is brutally honest: There’s a high likelihood we won’t save your home.”

Walter White, a fire chief in Amador County who served as a strike team leader for the Caldor Fire, said, “We had twice the amount of fire and half the resources on this as we did on the King Fire six years ago, which was in that same region. And a lot of that is because of staffing shortages.”

Officials with the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, or Cal Fire, said that “all fire resources, state, federal and local government, were drawn down” not due to understaffing but because several large fires were burning at the same time as Caldor. But local departments like Moore’s said firefighter shortages forced them to sit out many wildfires in addition to Caldor. In October alone, Moore turned down mutual aid requests for two other fires.

Meanwhile, firefighters on the ground reported that the lack of local crews — which can reach wildfires faster than state and federal responders — was allowing flames “to grow bigger and move more quickly into populated areas,” according to Sonoma County Fire District Chief Mark Heine, whose department joined the Caldor response in its early days.

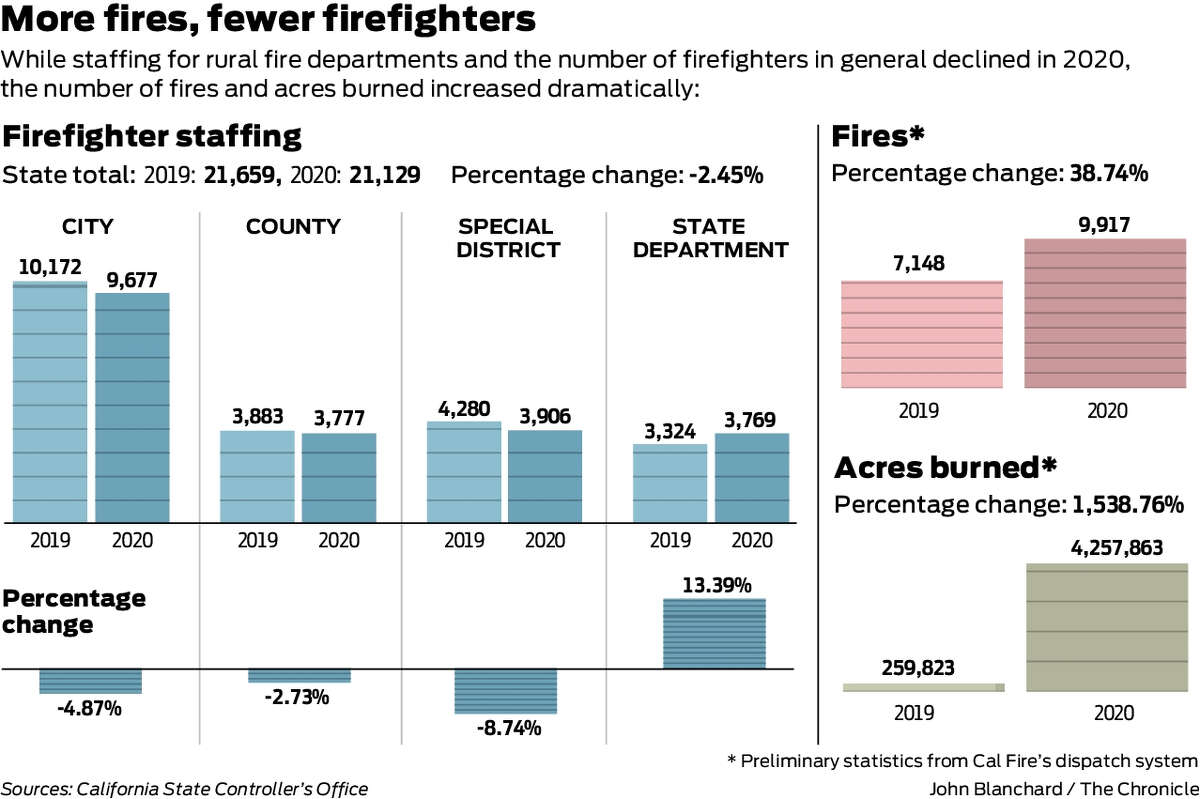

While the number of firefighters working in state agencies is growing, many of California’s city, county and special district fire departments are seeing their ranks plummet.

In 2020, state agencies — including Cal Fire, California State Parks and the California National Guard — added about 440 new firefighters, according to the California State Controller’s Office. That same year, local departments, which employ about 80% of the state’s firefighting force, lost more than 1,000 personnel.

The physical and emotional toll of the pandemic drove many firefighters in California to take early retirement, local fire chiefs say. The number of new applicants also dropped, forcing departments to compete to fill their vacancies.

In July 2018, the California State Fire Training Program, which certifies firefighters across the state, said it

issued 50,000 diplomas. In June 2020, that number had dropped by 16%, to about 42,000, according to the program’s

annual report.

State Fire Marshal Mike Richwine attributed the drop to delays in student certification driven by the pandemic. But some fire chiefs believe there are other factors at play.

In Auburn in Placer County, Fire Captain Matt Bowers said his department “can’t get people to even show up at the front door” to apply for new positions. The department’s chief, Dave Spencer, said recent shortages may boil down to generational changes.

Spencer suspects that younger people are looking for professions that offer better work-life balance. “I think the intrinsic value (of this profession) doesn’t necessarily translate across all generations. The Baby Boomers, they learned (to) put in a day’s work for a day’s wages. That doesn’t apply anymore today.”

As the pandemic drags on, urban fire departments appear to be steadily filling new vacancies while suburban and rural departments — which typically offer fewer benefits and $20,000 to $50,000 less in annual wages, according to employment records — are struggling.

Kevin McNally, deputy chief at the City of Palo Alto Fire Department — one of the state’s highest-paying fire agencies — said his department is “on the mend” after experiencing a year of staffing shortages. Many applicants, he said, are rural firefighters seeking salary boosts.

“Folks who come from the Central Valley and (northern rural areas) beyond can double their salaries here,” said McNally, who expects to fill the department’s vacancies well before next fire season.

Meanwhile, the Amador Fire Protection District, an eight-station department that serves a mostly rural county of nearly 500 square miles, has lost eight firefighters — a third of its active workforce — in the past six months, most of them to urban fire departments. Chief White said it will take months to find replacements.

Three firefighters who recently left White’s department joined a class of 500 firefighter candidates at the Sacramento Metropolitan Fire District academy — a pipeline program that directly staffs that city’s department every year. Thanks to the academy, any firefighter vacancies still outstanding at Sac Metro Fire were filled earlier this month as 20 diplomas were handed out, according to Parker Wilbourn, a captain at the department.

On top of staffing challenges, White said his department is also facing waves of sick leaves due to COVID-19. Seven Amador firefighters were at home for several days in October due to suspected or confirmed infections.

The state’s ongoing prison depopulation efforts, accelerated in recent times by concerns of COVID-19 spread, are cutting into the availability of inmate firefighters, a critical source of support for local fire agencies.

An award case on display at the Susanville Fire Department.

Max Whittaker/The Chronicle

Eight of the state’s 43 inmate firefighter training camps have closed or are

set to be shut down by next year. Inmate fire crews in the state have already shrunk from a total of 2,800 persons last year to about half that in October 2021, according to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation.

Robert Brown, a captain at the Susanville Fire Department, termed the closing of the camps “scary.” Susanville will lose a crew of six inmates assigned to it — one-fourth of its active responders — when the firefighting camp at the California Correctional Center shuts down next year.

Susanville is also one of more than 600 fire departments in California — two-thirds of the state’s total — that employ volunteer firefighters, according to the Federal Emergency Management Agency. In many departments, volunteers have become “essential,” but Moore said his department cannot always rely on them.

“They have jobs,” he said. When Caldor hit, Moore said, his 15 volunteers “had just come off a 12-week run. … Their employers were saying, ‘Hey, can you give us some production for a couple of weeks before you leave again?’”

With fewer firefighters on hand, departments are being forced to rely on those who are available to meet the “constant staffing” standards enforced by the National Fire Protection Association and the U.S. Department of Labor’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Constant staffing protocols require agencies to fill a set number of seats on each engine or positions at a station, allowing no flexibility during staffing shortages.

In Susanville, some firefighters said they have worked from 20 to 50 consecutive days, sometimes including stretches of 72 hours straight, multiple times in the past two years. In Auburn, Chief Spencer said he has approved shifts of more than 96 hours. Amador Chief White said he has had to require some staff to cover multiple 120-hour shifts this year.

“We’re putting in per year roughly 800, 900 (hours annually) above that average 40-hour work week,” said Bowers in Auburn. “You basically just work two years away in a year.”

His colleague Captain Matt Jelle, who has a teenager, a toddler and a 1-year-old at home, said that for the past five years he has had to put his job before his family. He said he mostly sees his children when they visit the firehouse.

“At the end of the day, we’re like everybody else in this world. We’re trying to feed our families, feed our kids, make the mortgage payments and the vehicle payments,” said Jelle. “And my family, they make the sacrifice.”

In 2020, overtime pay for county and city firefighters, who annually work the most overtime in their profession in the state, grew by 6% and 17%, respectively. In special district departments, it surged by 23%.

“Everybody is facing the same issue,” said Sonoma District Chief Heine, who is growing concerned about the safety of his staff. “The primary concern with the rise in overtime is fatigue, stress, PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder). … It takes a toll on them.”

Firefighters said that all that overtime can lead to mistakes and higher rates of injury and illness. Andrew Jarrett, a firefighter in Susanville, said incidents like drivers falling asleep at the wheel and crews making bad decisions because they are not “as sharp” will likely become more frequent.

Some local departments said they need more state and federal funding to maintain and expand their staffs.

In California, local fire departments are mainly funded through area property taxes. Although federal agencies and Cal Fire have been ramping up grant funding in recent years, the awards benefit only a small number of rural departments in Northern California.

In 2021, the Federal Emergency Management Agency distributed over $55 million in awards known as SAFER grants, which specifically target local staffing shortages. But just 20% of the grants were awarded to departments in the Greater Sacramento and Northern California regions.

In August, Cal Fire announced that it would invest $160 million to fund so-called Early Action local fire projects. But those grants focus on fire-prevention efforts and do not provide funding for additional staff.

White said his Amador County department has received state grants to fund new equipment — which can free up money to fund staff increases — multiple years in a row. But last year the department was not selected.

“You can’t fund ongoing expenses with one-time, not-guaranteed money,” he said.

White believes local departments would better serve their communities if more of them were consolidated into larger, better-staffed agencies like Sac Metro Fire, which

formed in 2000 when 16 smaller fire departments merged.

But Bob Stimpson, mayor of Jackson, the Amador County seat, said it’s unlikely that consolidation will happen any time soon. Although some like White are trying to move forward with such a merger, Stimpson said there is significant opposition among local chiefs.

In 2008, the county passed a sales tax increase to create a pool of money for local fire departments. Stimpson said the tax has since “turned into nothing but a big bone for all the departments to fight over” and soured relationships between chiefs. In 2020, an Amador County grand jury investigation found that this “bitterness and acrimony” had escalated to the point of compromising the safety of local communities.

“A lot of the chiefs (think) they have little kingdoms. No one wants to give up their area,” said Stimpson.

One local chief, Ken Mackey at the Ione Fire Department, disagreed. He said he and many other chiefs in the county oppose the merger because of its cost. Mackey estimated that a consolidation would cost his department in Ione at least $90,000.

“We are not fighting about anything,” he said. “They are trying to fix something that is not broken.”

Susanville firefighter Andrew Jarrett prepares to head back to the station after responding to an attic fire.

Max Whittaker/The Chronicle

If consolidation efforts fail, fire departments in Amador County would be forced to rely on property tax increases. But both Stimpson and White said any tax initiative would likely prove highly unpopular.

“I think people at this point are kind of tired of being taxed,” said Stimpson. “Maybe it would take something bad like the (2015) Butte Fire to change people’s minds.”

For three years, Moore has been pushing Susanville residents to pass a tax measure to better fund his department and make it

more appealing to prospective applicants by raising base wages and providing better benefits and retirement plans. But measures to do so were rejected in 2018 and 2020.

“People are standing on principle,” said Susanville City Administrator Dan Newton, who is working with Moore to put a measure on the ballot again in January. “There’s a significant level of mistrust toward the government in this region, (and) many rural regions like ours.”

Newton said the fate of the 2022 tax measure will define the future of the city’s fire services. Originally promoted as an initiative to enlarge the Fire Department, it’s become the city’s last-ditch attempt to save it.

Susanville currently owes a $15 million retirement debt to the California Public Employees’ Retirement System. If the measure — which would help relieve that liability — does not pass, the city would be forced to lay off more firefighters and other public safety employees to raise the necessary funds.

Moore is hopeful for a positive outcome, but is resigned to the idea that his community is not “ready, able, or willing to pay for the amount of firefighters” it would take to combat fire seasons like those he’s seen in the last two years. And he believes it’s only a matter of time before a wildfire hits his town.

Caroline Ghisolfi is a student in Stanford University’s M.A. program in journalism.